'Who is CPC?': Edgar Snow, the first Western journalist to introduce Red China to the world

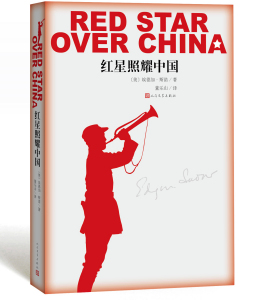

In October 1937, a newly published book became an instant hit in London, with more than 100,000 copies sold in just a few weeks and still much sought after following three additional printings. That book was Red Star Over China by Edgar Snow, an American journalist who first made the Communist Party of China (CPC) known to the world.

Red Star Over China

China in the 1930s was engulfed in the war against Japanese aggression. After the cooperation between the Kuomintang and the CPC broke down, the Kuomintang started a cleansing campaign against the CPC who had to take the Central Red Army on a long march that finally took them to Northern Shaanxi (known as Shaanbei) in October 1935. Yan'an, a small town in Shaanbei and then the base of the CPC, was like an islet surrounded by the ocean of the Kuomintang's military and information blockage. The world knew little about the CPC and the Red Army but the demonized images propagated by the Kuomintang.

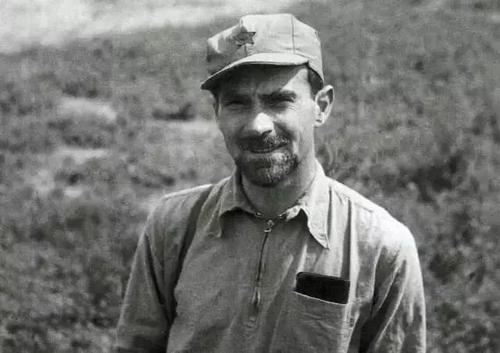

Snow in Shaanbei

What were the Chinese Communists like? And why so many Chinese people were willing to risk their lives to join the CPC and the Red Army? Snow's journalist instinct told him that Yan'an behind the Kuomintang's Great Wall of blockage was the only newsworthy story in China and that he had to go no matter what it took. With the help of Madame Soong Ching Ling, Snow set out for Yan'an. On July 13, 1936, after a long and difficult journey, he made it to Bao'an, a village in Yan'an where the CPC Central Committee was based.

That very night, he met Mao Zedong. In the house cave (Yaodong) and by the flickering candlelight, the two of them spent many nights talking, often starting at about 9 o'clock in the evening until the crack of dawn. During these conversations, Mao Zedong recounted for the first time the birth and growth of the Red Army, and the development of CPC bases and its policies; first shared his prediction of the Sino-Japanese war and China's ultimate victory; elaborated on the CPC's stance for a national united front against Japan and its sincerity in cooperation with the Kuomintang;and for the first time shared his views on the CPC and international issues,expounded on the Chinese Soviet Government's diplomacy, and China's readiness to seek stronger cooperation with friendly countries based on mutual respect.

Snow was deeply impressed by the ideals of Chinese Communists and Mao Zedong's charisma and knowledge. He saw Mao Zedong's experience as a microcosm of a whole generation of Chinese people. What made Mao Zedong different was that when he spoke, he was speaking for the ordinary Chinese, especially peasants. Snow later described these talks as the most valuable ones in his lifetime.

Zhou Enlai promised Snow he could write about anything he saw and had personally made him a 92-day interview plan. Snow was able to talk to over a hundred Red Army commanders, interviewed soldiers at the front line and recorded their daily life. He also engaged extensively with everyday people. Snow's authentic, first-hand reports presented vastly different pictures as opposed to the Kuomintang propaganda: Mao Zedong, who led the Red Army for a decade, had little personal property other than his quilt and a few clothes, and he refused to wear shoes if the soldiers had none; Zhou Enlai's "only luxury observable" was the mosquito net hanging over his clay bed; Peng Dehuai had a vest made of parachute cloth; and Lin Boqu, the "Minister of the Treasury", used strings to fasten his broken glass frame onto his ears.

Most Red Army soldiers were peasants and workers who joined to "help the poor and save China". Officers and soldiers were equal, and the casualty rate was high among commanders as they fought side by side with soldiers. The ruddy-faced young soldiers were, as Snow observed, "cheerful, gay, and energetic". In the Soviet Area, schools were opened to provide free education to poor kids. Theaters were free of charge with no exclusive seating or luxury boxes, with officials usually sitting among the audiences. Children called the Red Army "our army". Peasants referred to the government of the Soviet Area as "our government". There were no opium, corruption, slavery or begging. The freedom of marriage was respected and protected. In every Muslim neighborhood they stayed, the Red Army helped guard and clean the mosques. People were impressed by "their careful policy of respecting Islamic institutions", even the most suspicious ones among peasants and imams, according to Snow.

When asked by Snow, "What do you think of the Red Army", a bare-footed farmer boy said, "The Red Army is the army for poor people, and they fight for our rights". And when asked "How do you know they liked the Reds", the soldiers answered, "They made us a thousand, ten thousands, of shoes, with their own hands. Every home sent sons to our Red Army." "We, the Red Army, are the people."

After over 100 days in Shaanbei, Snow found the answer he had been looking for. He was fascinated by this unique charm of the East, something he believed representing the light of rejuvenation for the ancient nation of China. For him, the Communists were the most outstanding men and women he had met in China in the past decade with the "military discipline, political morale, and the will to victory", and "for sheer dogged endurance, and ability to stand hardship without complaint", they were "unbeatable". He recalled his four-month time with the Red Army as a most inspiring experience, during which he had met with the most free and happy Chinese he'd ever known. In these people who devoted themselves to what they believed was the right and just cause, Snow felt a vibrant hope, passion and the unbeatable strength of mankind, something he had never felt again ever since.

In the preface to the Chinese edition of Red Star Over China, Snow attributed the global popularity of the book not to its style or form, but the stories. According to him, the stories were created by the young Chinese revolutionaries and based on the accounts of Mao Zedong, Peng Dehuai, Zhou Enlai and many others. What he did was simply writing them down in words as fair as the water running in spring. The spirit, strength, desire and passion that made these people invincible represented the richest and most glorious of human history.

After returning to the United States, Snow continued to share stories about China's war against Japanese aggression in his country and with the world. He regarded the Chinese people's cause as one for truth, fairness and justice. Snow went back to China in 1970, standing side by side with Mao Zedong on the Tian'anmen gate tower. That moment was the highlight of his life-long bond with China's revolution.

In 1972, one week before his death, Snow was visited by Huang Hua, then China's permanent representative to the United Nations, who took a detour to Geneva en route to New York. Huang brought Snow Mao Zedong's regards. George Hatem, a doctor sent by Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai to care for Snow, recalled, "The two of us (Hatem and Huang) and Snow had spent so many days and nights in the house caves in Bao'an… Snow recognized us instantly. He sat up in surprise and said, 'Great! Now the three Red Gangsters are reunited!' We both burst in laughter with him."

Today, by the lake in Peking University, one of China's most prestigious institutions of higher learning, there is a gravestone with the epitaph that reads, "In Memory of Edgar Snow, An American Friend of the Chinese People", written in both Chinese and English. Snow never hid his love for China. He is now resting in peace in China — as he wished in his will — a land that he deeply loves and where he is loved.